The Cry of Dolores: Mexico’s Path to Independence

The Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821) represented a revolutionary struggle against Spanish colonial domination, unfolding through successive uprisings, military campaigns, and geopolitical tensions. Beginning with Miguel Hidalgo’s 1810 insurrection and culminating in the establishment of the First Mexican Empire, this eleven-year conflict involved complex alliances, ideological divisions, and shifting battlefronts. This article explores the significant events and key individuals, particularly focusing on the Cry of Dolores and its pivotal role in shaping Mexico’s struggle for independence.

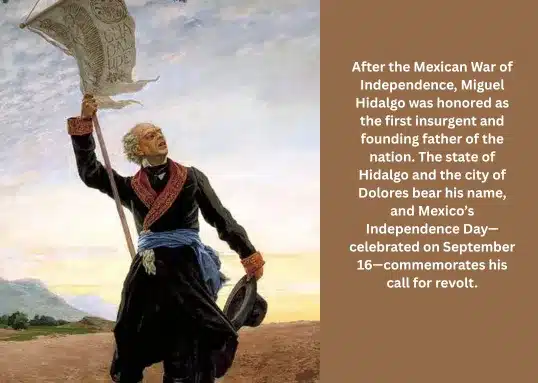

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, born in 1753, served as a Roman Catholic priest in Mexico and is recognized as the “father of Mexican independence.” He came from humble beginnings, attending a Jesuit school and eventually becoming ordained as a priest in 1778. Initially, he led a rather uneventful life.

Influenced by Enlightenment ideas, Hidalgo faced trouble in 1792, leading to his removal from his position. After his time in churches in Colima and Dolores, Hidalgo was inspired by the region’s rich soil and sought to help the underprivileged by teaching them how to grow olives and grapes. However, colonial authorities in New Spain forbade these crops to avoid competition with imports from Spain.

On September 16, 1810, Hidalgo delivered the Cry of Dolores, urging the people to defend King Ferdinand VII and revolt against the European-born Spaniards who had deposed the Viceroy José de Iturrigaray. He rallied around 90,000 impoverished farmers and civilians for a march across Mexico, but his ill-equipped and poorly trained forces faced well-prepared Spanish troops at the Battle of Calderón Bridge, resulting in a decisive defeat that underscored the significant challenges ahead in the struggle for independence.

💻 Table of Contents:

- Geopolitical Impacts: The Peninsular War Fueled the Mexican War of Independence

- Economic Factors behind the Mexican War of Independence

- Hidalgo and Morelos: Military Minds Behind the Independence War

- U.S. Reactions and the Mexican War of Independence after the Cry of Dolores

- Collapse of the First Mexican Empire and Foreign Interventions

- The Spanish Attempts to Reconquer Mexico

- Mexican Independence and the French Intervention

- Mexico’s Territorial Losses in the Early Independence Era

- Military Role of Indigenous Communities in Mexico’s Independence

- Afro-Mexican Contributions to the Mexican War of Independence

Geopolitical Impacts: The Peninsular War Fueled the Mexican War of Independence

The Peninsular War, triggered by Napoleon’s invasion and occupation of Spain from 1808 to 1813, heightened the revolutionary fervor in Mexico and other Spanish colonies. This conflict created a legitimacy crisis for the Spanish monarchy. With Joseph Bonaparte on the throne, Spanish authority weakened significantly, leaving a power vacuum that allowed independence movements in colonies like New Spain (Mexico) to gain momentum.

Amid the political instability, Creole elites in Mexico began to question their loyalty to the weakened Spanish crown. This rising nationalism fueled aspirations for an independent Mexico, as they envisioned a future free from Spanish control. The desire for self-governance grew stronger during this tumultuous period.

The context of the war led to armed rebellions, beginning with Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla’s revolt in 1810, which, despite its initial failure, ignited a decade-long struggle for independence. Shifting allegiances, exemplified by figures like Agustín de Iturbide, played a crucial role, ultimately culminating in Mexico’s declaration of independence in 1821.

Economic Factors behind the Mexican War of Independence

The economic oppression of New Spain’s colonial system fueled revolutionary fervor through heavy taxation, trade restrictions, and wealth inequality. Spanish policies stifled local industries while extracting silver and agricultural wealth, thereby burdening Indigenous and mestizo populations with poverty, while Creole elites profited. Bans on crops like grapes and olives prevented economic self-sufficiency, rendering colonial exploitation unbearable for the lower classes.

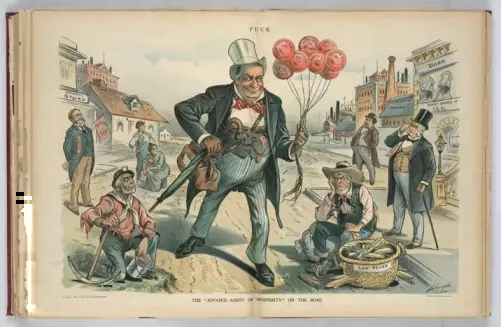

Mining and agriculture drove New Spain’s economy, yet profits flowed to Spain rather than local development. The Bourbon reforms of the 1700s eased some trade restrictions but failed to address systemic inequality, leaving the Church and elite landowners controlling most wealth. Meanwhile, food shortages and inflation worsened public discontent, turning economic hardship into a rallying cry for independence.

By the early 1800s, colonial resentment reached a breaking point. The crippling tax system, combined with Enlightenment ideals of economic freedom, pushed reformers like Hidalgo to demand change. The commitment to equitable resource distribution and the elimination of Spanish monopolies became key issues in the Mexican War of Independence. After three centuries of peace, the colony was ready to rule itself. When revolutionary ideas from America and France spread, they ignited Mexico’s push for independence, fighting not only for political freedom but also for economic justice.

Hidalgo and Morelos: Military Minds Behind the Independence War

The Battle of Calderón Bridge took place on January 17, 1811, during the Mexican War of Independence. Following a failed attempt by Father Miguel Hidalgo to capture Mexico City, the insurgent army retreated towards Guadalajara, where they fortified at Calderón Bridge. They faced an 8,000-strong Royalist army led by Félix María Calleja. The Royalists, composed of professional soldiers, defeated the disorganized insurgents, and the explosion of an insurgent munitions wagon led to a rout.

On July 30, 1811, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was executed by a firing squad in Chihuahua, marking the end of his direct involvement in the Mexican War of Independence. His death dealt a significant blow to the movement, but his actions and leadership inspired many in their quest for freedom from Spanish rule. Today, he is celebrated as a national hero and a symbol of Mexican independence.

After Hidalgo’s capture, José María Morelos, another priest and skilled military strategist, took over leadership of the independence movement. Under his command, the rebellion shifted southward and began to gain momentum.

Morelos, coming from a diverse ethnic background in a society that strictly categorized people by ethnicity, began his studies to become a priest at the Colegio de San Nicolás in Valladolid at the age of 25. After his ordination, he served primarily indigenous and mixed-race communities and joined Miguel Hidalgo’s rebellion in 1811. Following Hidalgo’s death, Morelos took command of the movement in southern Mexico.

To formalize the independence struggle, Morelos convened the Congress of Anahuac, the first independent Mexican congress, which officially declared Mexico’s independence from Spain. In September 1813, he presented the founding document of independent Mexico, known as the “Sentiments of the Nation.” This document, drafted by José María Morelos, served as the foundation for the Independence Act of 1813. This historic document not only abolished slavery and racial distinctions.

Between 1812 and 1815, Morelos controlled a significant part of southwestern Mexico, including places like Acapulco, Oaxaca, Tehuacán, and Cuautla (Santiago Cuautla). However, he didn’t have enough manpower to keep control over all of these areas, so he started using guerrilla tactics, which are hit-and-run strategies.

Eventually, the royalist forces caught up with the rebels. Although Morelos fought valiantly to protect the congress, he was captured. Morelos was sentenced to death and executed by a firing squad on December 22, 1815, in San Cristóbal Ecatepec, located north of Mexico City.

U.S. Reactions and the Mexican War of Independence after the Cry of Dolores

Following the Cry of Dolores in 1810, the United States watched Mexico’s independence movement with interest. While the U.S. government remained officially neutral, many Americans sympathized with the rebels, seeing parallels to their own revolution. Some even provided informal support, sending volunteers and supplies to aid the insurgency. However, concerns about regional instability also shaped early U.S. attitudes toward Mexico’s struggle.

The fight for independence continued under leaders like Vicente Guerrero, a mixed-race insurgent who took command after Morelos’s execution in 1815. Guerrero’s guerrilla tactics and commitment to racial equality strengthened the movement. In 1821, former royalist Agustín de Iturbide allied with Guerrero, drafting the Plan of Iguala, which called for an independent Mexico under a constitutional monarchy.

The Treaty of Córdoba, signed on August 24, 1821, formally recognized Mexico’s independence, marking the end of Spanish rule. The treaty solidified the principles of the Plan of Iguala, uniting different factions under a shared vision of sovereignty. This victory not only reshaped Mexico’s future but also set the stage for its evolving relationship with the United States.

Collapse of the First Mexican Empire and Foreign Interventions

The Plan of Iguala paved the way for the creation of the First Mexican Empire, with Agustín de Iturbide as its emperor and Guerrero as a prominent military leader. Despite its initial promise, the empire faced internal and external challenges, and by 1822, Iturbide’s increasingly authoritarian rule led to widespread discontent among various groups. This led to a power struggle, and by 1823, Iturbide was forced into exile, and the First Mexican Empire collapsed.

The First Mexican Empire, established under Agustín de Iturbide in 1821, quickly fell apart due to his authoritarian rule. By 1823, Iturbide was overthrown and exiled, leading to political chaos. Vicente Guerrero, a key independence leader, later became president in 1829 after a disputed election, focusing on social reforms but facing ongoing instability.

Spain attempted to reconquer Mexico in 1829 but was defeated at the Battle of Tampico by Antonio López de Santa Anna, who became a national hero. Spain finally recognized Mexico’s independence in 1836. However, foreign threats continued when France invaded in 1862, installing Maximilian I as emperor during the Second Mexican Empire.

Mexican republicans, under the leadership of Benito Juárez, opposed French rule, viewing it as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, with support from the United States. Despite Maximilian’s reforms, his regime collapsed in 1867, restoring the Mexican Republic. These conflicts highlighted Mexico’s struggle to maintain sovereignty amid internal divisions and foreign interference.

The Spanish Attempts to Reconquer Mexico

The Plan of Iguala led to the establishment of the First Mexican Empire, with Agustín de Iturbide becoming emperor and Vicente Guerrero emerging as a key military leader. However, the empire was short-lived, facing internal and external challenges. In 1822, Iturbide’s rule became increasingly authoritarian, causing discontent among various groups. This led to a power struggle, and by 1823, Iturbide was forced into exile, and the First Mexican Empire collapsed.

After Iturbide’s fall, Mexico experienced political instability. Different factions and leaders vied for power, and Guerrero was involved in various conflicts. Presidential Election of 1828: In 1828, Mexico held its first presidential election, and Vicente Guerrero was one of the candidates. However, the election results were disputed, and Manuel Gomez Pedraza was declared the winner.

Guerrero and his supporters were unhappy with the election results, and he led a revolt against the government in December 1828. This revolt marked the beginning of a series of conflicts known as the “Guerrero Campaign.” As a result of the revolt and ensuing political changes, Guerrero assumed the presidency on April 1, 1829. His presidency was characterized by efforts to promote social justice and equality.

💻 You May Also Read:

- The Spanish-American War: Roots in US Envision of Great Power Status

- Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: Redefining the US-Mexico Border

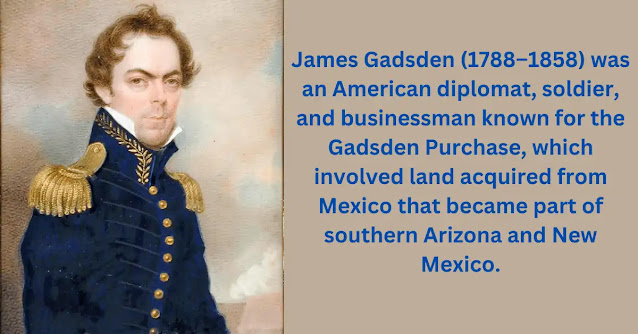

- The Gadsden Purchase: Exploring US Land, Politics and Strategy

After Mexico gained independence in 1821, Spain sought to regain its former territory, motivated by Mexico’s wealth and strategic significance. In 1829, Spanish General Isidro Barradas led an invasion with over 3,500 soldiers but was decisively defeated by Mexican forces under General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna at the Battle of Tampico. This failed attempt marked Spain’s last military effort to reconquer Mexico; it was only in 1836 that Spain officially recognized Mexico’s lasting independence through the Santa Maria-Calatrava Treaty.

Mexican Independence and the French Intervention

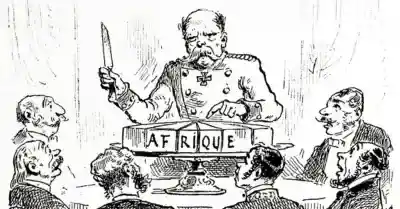

In 1862, French Emperor Napoleon III sought to establish a client state in Mexico by installing Maximilian of Habsburg as emperor amid a backdrop of civil war between Liberal and Conservative factions. The United States, recovering from its Civil War, initially adopted a cautious stance, prioritizing relations with France to prevent support for the Confederacy. As European powers intervened, Juárez’s government faced significant challenges, ultimately leading to a tripartite agreement among France, Spain, and Britain to recover debts, which escalated into full-blown French intervention.

By 1865, the tide turned as Juárez’s forces gained strength, coinciding with the end of the American Civil War. U.S. support for Juárez increased, and Napoleon III, facing domestic unpopularity and financial strain, ordered the withdrawal of French troops. Maximilian’s failure to consolidate power and gain local support led to his capture and execution in 1867, marking the end of foreign intervention in Mexico. This period highlighted the complexities of U.S.-Mexican relations and the shifting balance of power in the Americas.

Benito Juárez, regarded as one of Mexico’s greatest leaders, refused to accept foreign rule during the French occupation, striving to establish Mexico as a constitutional democracy while promoting equal rights and social reforms. His decision to suspend payments on foreign debts angered European creditors, leading to the French invasion in late 1861, supported initially by Britain and Spain.

The U.S. viewed this as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine but was unable to intervene during the Civil War. After the conflict, President Andrew Johnson demanded the withdrawal of French troops, which facilitated a series of victories for Juárez’s Republicans. Ultimately, Maximilian was captured and executed in June 1867, solidifying Juárez’s authority and marking the end of foreign intervention in Mexico.

Mexico’s Territorial Losses in the Early Independence Era

Mexico’s early independence period was marked by political instability and territorial losses under President Antonio López de Santa Anna. In 1836, following defeat at the Battle of San Jacinto, Santa Anna—captured as a prisoner—was forced to recognize Texas’s independence. The situation worsened when Texas joined the United States in 1845, sparking a border dispute that led to the Mexican-American War (1846–1848).

The war proved disastrous for Mexico, resulting in the loss of over half its territory through the Mexican Cession (1848), which included present-day California, Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of other southwestern U.S. states. Just five years later, Santa Anna further diminished Mexico’s land by selling what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico in the Gadsden Purchase (1854), allegedly to fund a railroad and settle lingering border issues, while also enriching himself.

These territorial losses reshaped both nations, establishing the modern U.S.-Mexico border through successive agreements. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in particular, not only redefined the physical boundary but also guaranteed rights for Mexican citizens remaining in the ceded territories, though these protections were often ignored. For Mexico, these defeats underscored the challenges of maintaining sovereignty amid internal instability and external pressure, leaving a lasting impact on its national identity and geopolitical standing.

Military Role of Indigenous Communities in Mexico’s Independence

Indigenous militias played a vital yet often overlooked role in Mexico’s War of Independence (1810–1821). Employing guerrilla tactics and leveraging their deep knowledge of local terrain, these forces disrupted Spanish colonial rule and supported key revolutionary leaders like Hidalgo and Morelos. Despite their crucial contributions, Indigenous fighters were largely excluded from post-independence power structures, as the new Mexican state failed to address their demands for land rights and political inclusion.

Today, the legacy of these militias lives on in modern Indigenous movements, such as the Zapatista uprising, which draws inspiration from centuries of resistance. Their struggle for recognition and justice continues to shape Mexico’s national identity, reminding society of the unresolved inequalities rooted in colonial history. The fight for Indigenous rights remains a powerful testament to their enduring influence on Mexico’s past and present.

Afro-Mexican Contributions to the Mexican War of Independence

Afro-Mexicans played a crucial yet often overlooked role in Mexico’s fight for independence (1810–1821). As part of the mixed-race caste system under Spanish rule, Afro-Mexicans faced systemic oppression, including slavery and racial discrimination. Many joined the insurgent forces, contributing military strength and leadership to the revolutionary cause. Figures like Vicente Guerrero, a mixed-race (mulato) independence leader, emerged as key commanders, proving that the struggle for freedom transcended racial divisions.

💻 Table of Contents:

- American Civil War: A Turning Point for Democracy

- The Monroe Doctrine: American Plan for the Americas

- Manifest Destiny: Geopolitical Doctrine behind U.S. Expansion

Vicente Guerrero, of African and Indigenous descent, became one of the most prominent insurgent generals, later rising to Mexico’s presidency in 1829. His famous declaration—“My Motherland comes first”—symbolized his commitment to liberation over personal gain. As president, Guerrero abolished slavery, a landmark decree that challenged colonial-era racial hierarchies. However, his progressive policies angered conservative elites and foreign slaveholding interests, particularly in Texas, where resistance to his abolitionist stance fueled future tensions.

The legacy of Afro-Mexicans in the independence movement remains vital to understanding Mexico’s multicultural roots. Though their contributions were marginalized in official histories, their fight for equality helped shape the nation’s identity. Today, Guerrero’s leadership and the broader Afro-Mexican resistance serve as enduring symbols of courage and justice in Mexico’s ongoing struggle for social inclusion.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Revolution and Its Modern Echoes

While the Mexican War of Independence ended Spanish rule, it fell short of achieving social equality, economic justice, and genuine self-determination. Marginalized groups, such as indigenous and Afro-Mexican communities, were excluded from power, setting the stage for future conflicts like the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Centralization in Mexico City exacerbated regional disparities, a tension that still fuels debates over federalism.

The movement’s legacy offers insights for global decolonization efforts, highlighting the complexities of local agency amid geopolitical dynamics. Untold stories, such as the role of rural militias and the suppression of agrarian reforms, remind us that liberation is not merely about breaking free but also about rebuilding systems. As Mexico faces modern challenges, the independence era serves as a poignant reminder that true freedom requires ongoing commitment to equity and justice.