Scramble for Africa: Insights from the Berlin Conference

The Prior to the 1880s, European presence in Africa was primarily limited to coastal trading posts and scattered territorial footholds. Britain maintained strategic settlements in Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast (modern Ghana) and Southern Africa, while France held key positions in Senegal and Algeria. Portugal retained its centuries-old bases in Angola and Mozambique, Spain controlled small North African enclaves, and the Ottoman Empire exercised nominal authority over Egypt and Libya.

This fragmented colonial landscape, covering only about 10% of the continent, would soon be radically transformed. The Scramble for Africa was a race mostly between Britain, France, Portugal, Germany, Belgium, and Italy, to acquire colonies on the continent.

The Berlin Conference, which took place in 1884-1885, marked the start of the “Scramble for Africa,” leading to a rapid and systematic division of the continent among European powers. By 1914, nearly 90 percent of Africa had been absorbed into European empires. This article explores the complex causes behind this imperial rush, from industrial-era resource demands to inter-European rivalries. It further analyzes the devastating consequences of colonial exploitation and arbitrary border-making, while tracing how this period’s legacy continues to influence modern Africa’s political, economic, and social challenges.

Cartoon of Berlin Conference, Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Scramble fundamentally reshaped Africa’s place in world history, creating patterns of dependency and conflict that persist today. This term describes the swift invasion, occupation, and division of Africa by European powers from approximately 1880 to 1914, motivated largely by economic, political, and social factors. This period is also known as the Partition of Africa or the Race for Africa.

💻 Table of Contents:

- Mad Rush of the Early 1880s: Prelude to the Berlin Conference

- The Roots of European Colonization in Africa

- Russia’s Failed Colonial Ambitions in Africa

- The USA’s Absence from the Scramble for Africa

- The New Scramble for Africa: China’s Growing Influence

- Africa’s Artificial Divisions and Their Consequences

Mad Rush of the Early 1880s: Prelude to the Berlin Conference

European powers were engaged in a frenzied scramble for African territory in the early 1880s. France established protectorates in northern Congo and Tunisia, Britain seized control of Egypt, and Italy launched its colonization of Eritrea. Germany aggressively claimed four territories – South West Africa, Cameroon, German East Africa, and Togo – while Britain and France carved out Somaliland, and Spain asserted its claim over Río de Oro (modern Western Sahara). This unprecedented land grab brought the European powers dangerously close to conflict.

To regulate this chaotic competition, European nations followed the example set by Spain and Portugal centuries earlier by establishing formal rules for dividing the continent through a conference known as the Berlin Conference (1884-85), also known as the West Africa Conference or the Congo Conference. This conference brought together fourteen countries and resulted in the General Act of Berlin, which formalized the Scramble for Africa.

The Conference created a framework for colonization that included: free navigation of the Niger and Congo rivers; the principle of “effective occupation” to legitimize territorial claims; mandates to “civilize” protectorates through Christianity and trade; and requirements for military and administrative presence inland. These rules transformed Africa’s colonization from informal economic penetration to systematic political control.

The Conference marked a watershed moment. Prior to 1884, European involvement had focused on coastal trade and private commercial ventures. Afterwards, imperial powers rapidly established formal colonial administrations and intensified resource extraction. By 1913, the Conference’s ultimate goal was achieved: nearly all of Africa had been partitioned among European nations without triggering war between them. Only Liberia (a colony run by former African American slaves) and Ethiopia remained independent.

The “civilizing mission” proclaimed at Berlin served as a thin disguise for exploitation, as colonial powers redirected their violence against African populations rather than each other. The mad rush of the early 1880s had culminated in the continent’s wholesale subjugation – a colonial system that would persist until March 21, 1990, when Namibia, Africa’s last colony, finally achieved independence.

The Roots of European Colonization in Africa:

The Scramble for Africa did not emerge spontaneously, but grew from deep historical, economic, geopolitical and technological forces that transformed Europe’s relationship with the continent. This section examines the pivotal factors that enabled and accelerated the Scramble for Africa—from the abolition of the slave trade, which redirected European exploitation toward resource extraction, to the technological advancements that made conquest possible.

The Berlin Conference (1884-85) formalized this conquest under diplomatic guise, while Leopold II’s Congo Free State revealed its brutal reality. These foundations of colonial rule created lasting damage—artificial borders, economic dependency, and violence—that still haunt Africa today.

Effects of Ending the Slave Trade in Africa’s Colonization

The abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in the 19th century marked a pivotal shift in Europe’s relationship with Africa. While the move was intended to end human exploitation, it inadvertently paved the way for new forms of economic and political domination. European powers, no longer able to profit from the slave trade, turned their attention to extracting Africa’s natural resources and establishing colonial control. This transition was formalized at the Berlin Conference (1884–85), where European nations partitioned the continent without African input, laying the groundwork for systematic exploitation through forced labor, cash-crop agriculture, and mineral extraction.

The end of the slave trade did not liberate Africa; instead, it redefined its subjugation and set the stage for subsequent colonial conquest by European powers. While some African societies resisted, the military and technological superiority of European powers ensured their dominance. The colonial era left a legacy of economic dependency and disrupted social structures, which persisted even after independence movements succeeded in the mid-20th century. Ultimately, the abolition of slavery became a catalyst for a new, equally exploitative system of colonial capitalism that reshaped Africa’s trajectory.

The Congo Free State: Leopold II’s Personal Colony of Terror

The early 19th century saw European explorers venture into North Africa, driven by curiosity and the allure of uncovering the secrets of the Sahara Desert. As Ottoman control over coastal regions waned, expeditions such as those led by Walter Oudney, Hugh Clapperton, and Dixon Denham (1823) mapped the Niger River and reached Lake Chad. The fabled city of Timbuktu also drew explorers like Gordon Laing and René Caillié, though their accounts revealed its modest reality, dispelling myths of grandeur. These journeys laid the groundwork for later colonial ambitions in the region.

However, as the century progressed, exploration became less about discovery and more about economic exploitation. European adventurers began meticulously documenting Africa’s markets, resources, and trade potential, laying the groundwork for colonial ambitions. These expeditions transformed into reconnaissance missions, providing European powers with the intelligence needed to justify and facilitate their imperial designs.

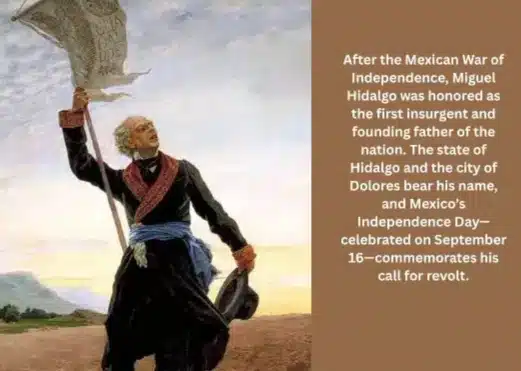

The role of individuals like Henry Morton Stanley proved pivotal in accelerating the Scramble for Africa. Commissioned by Belgium’s King Leopold II, Stanley secured treaties with Congolese chieftains, enabling Leopold to claim the Congo as his personal fiefdom—the infamously brutal Congo Free State.

“Civilisation” was at the core of Leopold II’s pitch to European leaders in 1885, as they carved up Africa at the Berlin Conference. Under the guise of humanitarianism, he secured 2 million square kilometers to create the Congo Free State—a territory he ruled as a private enterprise, not a Belgian colony. Promises of progress hid the reality of forced labor, where people in Congo were hurt badly to gather rubber, ivory, and minerals. Archival evidence reveals systemic atrocities: children kidnapped for labor camps, villages decimated by punitive raids, and a death toll estimated at 10 million from killings, famine, and disease.

Though Leopold never visited, his regime’s profits enriched both Belgium and his personal coffers. International outcry eventually exposed the hypocrisy of his “civilizing mission,” forcing him to relinquish control in 1908—but not before the Congo’s wealth and people paid a staggering price. The Congo Free State’s horrors became a symbol of colonial brutality, underscoring how Europe’s “Scramble for Africa” prioritized exploitation over liberation.

Capitalism: A Crucial Role in the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa (1885–1914) was fundamentally driven by capitalist imperatives, as industrialized European powers sought to exploit the continent’s untapped resources to fuel their economies. Under the guise of “New Imperialism,” nations like Britain, France, and Belgium avoided intra-European conflict by targeting Africa as a “safety valve,” using military force, exploitative trade, and missionary activities to establish control.

The Berlin Conference (1884–85) formalized this division, with European powers claiming 30% (Britain), 15% (France), and 9% (Belgium) of Africa’s population—all to secure rubber, minerals, and cash crops. This economic plunder triggered a Naval Arms Race and the Entente Cordiale, exacerbating tensions that later contributed to World War I. Capitalism’s demand for raw materials thus reshaped global politics while reducing Africa to a resource periphery.

💻 You May Also Read:

- The British-Dutch Battle in South Africa: A Clash of Empires

- The Geopolitical Connection: Italian Eritrea and the British-Ethiopian Part

- German East Africa: A Window into the History of Tanzania and the British Part

African economies, engineered to serve European factories rather than domestic needs, remain disproportionately reliant on raw exports. The Scramble’s machinery, masked as “civilizing missions,” revealed how economic greed could reshape continents and condemn generations to underdevelopment.

Technological Advances: The Forces Behind Africa’s Exploitation

The development of steam engines and iron-hulled boats like Britain’s Nemesis (1840) transformed European access to Africa. These vessels could navigate inland rivers, allowing explorers such as Livingstone and Stanley to map the continent’s interior and open paths for military control. The 1817 discovery of quinine reduced malaria deaths among Europeans, while steam transport enabled faster movement of troops and resources. Together, these breakthroughs overcame Africa’s natural barriers to foreign invasion.

European military technology also saw crucial advances. While early 1800s weaponry offered only modest advantages, new percussion caps and breech-loading rifles later gave colonial forces overwhelming firepower. Combined with policies limiting African access to modern arms, these innovations ensured European dominance during rapid colonization.

These technological tools served conquest rather than progress. Steamships became gunboats, quinine protected only colonizers, and advanced weapons enforced submission. What began as exploration tools became instruments of control, making Africa vulnerable to systematic exploitation through technological superiority alone.

Bismarck’s Blueprint: A Conference That Divided a Continent

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s 1884-85 Berlin Conference sought to prevent European conflicts over African territories while advancing Germany’s strategic interests—not through direct colonization, but by regulating others’ ambitions. Bismarck, initially indifferent to overseas colonies, aimed to stabilize Europe by establishing rules for African claims: “effective occupation,” free trade zones, and mutual recognition of borders.

Yet these very mechanisms—designed to manage competition—accelerated the Scramble for Africa. By legalizing territorial grabs under the guise of order, the conference gave European powers like France and Britain a roadmap to carve up the continent, while Germany later joined the race to secure its own colonies.

The conference’s legacy was paradoxical. While it averted immediate European wars, it unleashed systematic exploitation in Africa. The principle of “effective occupation” justified military conquests, while “free trade” masked resource extraction that enriched Europe at Africa’s expense. Bismarck’s realpolitik—prioritizing European peace over African sovereignty—set the stage for colonial brutality, dispossession, and artificial borders whose conflicts endure today. The Berlin Conference thus proved that even a reluctant imperialist could ignite an era of domination, revealing how Europe’s “orderly” diplomacy became Africa’s chaos.

Russia’s Failed Colonial Ambitions in Africa:

Despite modern claims of anti-colonialism, the Russian Empire actively sought to colonize parts of Africa during the late 19th century, though its efforts ended in failure. Adventurers like Nikolai Ashinov and Nikolai Leontiev spearheaded unofficial colonial ventures, with Ashinov attempting to establish “New Moscow” in present-day Djibouti—only to be expelled by French forces. Leontiev, meanwhile, exploited Ethiopia under the guise of diplomacy, extracting resources and even briefly governing a southern province before being ousted.

While St. Petersburg distanced itself from these reckless schemes, archival records reveal that Russian officials viewed Africa as a potential zone of imperial expansion, driven by the same racist and exploitative motives as other European powers.

Russia’s 1897 mission to Ethiopia revealed its true colonial goals, with envoys describing Africans in degrading terms and proposing military bases to counter British influence. However, Ethiopia’s shrewd leadership, combined with Russia’s military and economic limitations, thwarted these ambitions. Defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1905) and internal unrest forced Russia to abandon its African designs, leaving it as a marginal player in the Scramble for Africa.

Furthermore, internal challenges, including social reforms and industrialization, demanded attention. Besides, Russia’s geographic constraints, competing imperial ambitions, and weaker naval capabilities kept it from becoming a major participant in the colonization of Africa. Today, the Kremlin whitewashes this history, falsely portraying Russia as an anti-colonial ally—a narrative that ignores its imperialist past and repeated failures on the continent.

The USA’s Absence from the Scramble for Africa:

The United States chose not to participate in the late 19th-century “Scramble for Africa” due to its commitment to the Monroe Doctrine, which opposed European colonization in the Western Hemisphere and discouraged American involvement in overseas imperialism. This policy, combined with the nation’s anti-colonial roots from the American Revolution, shaped its reluctance to engage in African colonization. Additionally, the USA prioritized domestic expansion and industrialization, focusing on westward growth rather than overseas territories. Geographic distance further reduced its incentive to compete with European powers for African land.

While the USA maintained limited economic ties with Africa—most notably in Liberia, founded as a settlement for freed African Americans—its primary focus remained on internal development. Political and social challenges, such as Reconstruction after the Civil War and rapid industrialization, demanded attention, leaving little room for colonial ambitions. Ultimately, the USA’s adherence to the Monroe Doctrine, its anti-imperialist tradition, and its domestic priorities kept it from joining European powers in the division of Africa.

The New Scramble for Africa: China’s Growing Influence

The “Scramble for Africa” has taken on a new dimension with China’s increasing involvement in the continent’s development. Projects like the Addis Ababa Light Rapid Transit have transformed cities, showcasing China’s commitment to African infrastructure. In 2014, China signed over £56 billion in construction contracts across Africa, positioning itself as a key player in the continent’s growth.

Since the early 2000s, Chinese firms have built various infrastructure, including stadiums, highways, and hospitals, even creating an entire city in Angola that remains unoccupied. China has invested hundreds of billions in African infrastructure and governments, gaining significant returns in commodities. However, concerns about a new form of colonialism persist, as many question whether the relationship between China and African nations is truly equitable.

As the “Scramble for Africa” evolves, it highlights both opportunities and challenges for the continent. While China provides much-needed investment, the social and political implications of rapid development raise concerns. Ethiopia’s experience with the light railway illustrates the potential for unrest as local populations navigate the complexities of foreign partnerships. As Africa’s landscape shifts, the impact of this new scramble will continue to shape its future.

Africa’s Artificial Divisions and Their Consequences:

In the late 1800s, European powers divided Africa, creating borders without regard for the locations of various ethnic groups. New research indicates that this hasty border-drawing has led to lasting issues that persist today. Groups such as the Maasai, split between Kenya and Tanzania, and the Chewa, divided among three countries (Malawi, Zambia, and Mozambique), experience more frequent, prolonged, and violent conflicts compared to groups that were not divided.

The repercussions extend beyond these divided groups. When one group encounters violence, it often triggers unrest in neighboring communities. For instance, the mistreatment of the Alur people in Congo has also caused instability in Uganda. Furthermore, divided groups generally face greater economic challenges, with poorer living conditions and inadequate access to education and healthcare compared to other groups within the same country.

The research uncovers how Europe’s careless border-drawing in Africa still causes problems today. About 31% of divided groups have engaged in ethnic-based civil war, versus just 19% of non-divided groups. Similar issues likely exist in other regions, such as the Middle East, where colonial powers made similar mistakes. Addressing these historical errors is crucial for promoting peace and development in Africa’s future.

Legacy of the Scramble: The Impact of Artificial Borders

The Cold War transformed Africa’s decolonization into a superpower battleground. The USSR actively armed liberation movements like Angola’s MPLA, framing support as anti-imperialist solidarity. Meanwhile, the US prioritized containing communism, often backing authoritarian regimes such as Mobutu’s Zaire. Both powers exploited the Scramble’s unresolved tensions, turning newly independent states into proxy war zones.

This competition created devastating legacies. While Soviet weapons fueled revolutions, US support propped up dictators – all while African nations struggled for true sovereignty. The Scramble for Africa’s artificial borders became Cold War battlegrounds, showing how colonialism endured under new masters.

Following World War II, African nationalism surged, driving many nations toward independence by the 1970s. However, the paths to freedom varied, with some achieving peaceful transitions while others resorted to violent struggles.

Despite gaining political independence, many African nations grapple with the enduring legacy of colonialism, which has left them politically unstable and economically challenged. The artificial borders established during the Scramble for Africa have contributed to social divisions and conflicts. Meanwhile, the rise of Pan-Africanism emphasizes the importance of unity among African states, yet neocolonialism continues to hinder their quest for true sovereignty.

A recent UN report highlights how the Scramble for Africa’s colonial past fuels ongoing racism, discrimination, and inequality. Former colonies, particularly in the Global South, still face economic underdevelopment and unequal access to essential services. To address these deep-rooted injustices, experts advocate for transitional justice measures, including reparations and policy reforms, to dismantle the harmful legacies of colonialism and promote sustainable development worldwide.

Conclusion: The Enduring Shadow of the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was not just a historical event but a foundational trauma that continues to shape the continent’s destiny. The resistance of leaders like Menelik II and the tragic lessons of the Maji Maji Rebellion remind us that African agency was always present—even when overpowered by European military might. Meanwhile, the destruction of indigenous governance systems and forced labor economies created wounds that still require healing through truth, reparations, and the return of looted cultural heritage.

Today, Africa grapples with the paradox of political independence amid enduring foreign influence, from France’s Françafrique (a foreign policy between France and its former African colonies) system (a term used to describe the political, economic, and military relationships between France and its former African colonies) to China’s infrastructure-driven diplomacy. The voices of writers like Chinua Achebe and movements for artifact restitution prove that reckoning with colonialism remains unfinished business.

As climate change and global power struggles refocus attention on Africa’s resources, understanding the Scramble’s full impact—from gendered oppression to ecological plunder—is essential. Only by confronting these layered legacies can Africa and its global partners forge a more just future.