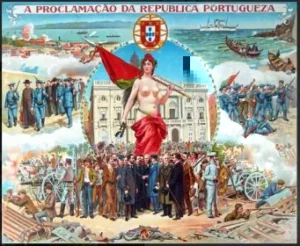

Revolt of the Sergeants: A Turning Point in Portuguese History

On January 31, 1891, a group of influential individuals in Porto, Portugal, led a revolt known as the “Revolt of the Sergeants” in an attempt to establish a republic. The revolt was driven by various factors, including the economic crisis, the British Ultimatum challenging Portuguese presence in Africa, and a sense of national humiliation.

The proclamation of a Republic in Brazil also served as inspiration for the uprising, fostering the belief that the republican model could bring about positive political and social changes. Despite lacking support from high-ranking officers, the sergeants rallied fellow soldiers and their objective was to capture the Post Office and Telegraphs, ultimately proclaiming the republic.

However, their plans were hindered by the loyal municipal guard near the Church of Santo Ildefonso. The remaining rebels sought refuge in the City Hall, where they proclaimed the republic from its balcony. Despite their efforts, the revolution was unsuccessful, and the rebels either fled abroad or were taken aboard ships at Leixões.

💻 Table of Contents:

- Brazil’s Republic to Portugal’s Revolt: A Transatlantic Inspiration

- Pink Map: Portugal’s Colonial Defeat and the Revolt of the Sergeants

- Anglo-German secret agreement on Portuguese Africa

- The Porto Republic Revolt: Soldiers Rise for a New Era

- From Defeat to Destiny: The Revolt of the Sergeants and Its Historical Legacy

The Republic would only be officially proclaimed in Portugal in 1910. The memory of this event is still commemorated today in the streets of Porto, with Rua 31 de Janeiro in downtown Porto and streets named after the individuals involved in the failed revolution, such as Alves da Veiga, Rodrigues de Freitas, and Alferes Malheiro.

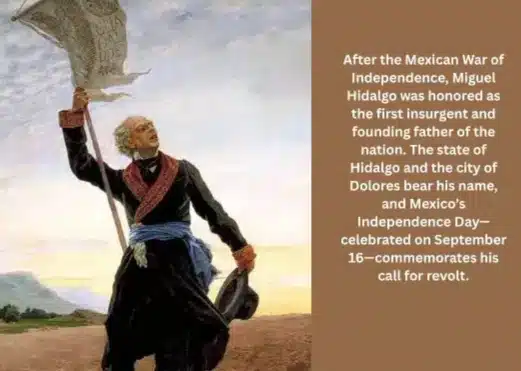

Brazil’s Republic to Portugal’s Revolt: A Transatlantic Inspiration

Following the upheaval caused by Napoleon’s invasion, the Portuguese monarchy’s relocation to Brazil (1808–1821) set in motion a century of political transformation on both sides of the Atlantic. The collapse of Brazil’s monarchy on 15 November 1889—when military leaders ousted Emperor Pedro II—resonated powerfully in Portugal. While not a direct cause, this event critically inspired Portugal’s Revolt of the Sergeants on 31 January 1891. Portuguese republicans, already disillusioned by their monarchy’s humiliation in the 1890 British Ultimatum, saw Brazil’s successful transition as proof that regime change was achievable. Though the Porto uprising failed militarily within hours, it became an ideological turning point—demonstrating that republican ideals could transcend borders and that Portugal’s centuries-old monarchy was vulnerable.

The parallels between these movements were striking. Both blended military discontent with civilian republican fervor: Brazil’s coup leaders and Portugal’s rebel sergeants shared a belief in armed action against monarchical “decadence.” Brazil’s abolition of slavery (1888) and rapid republican shift had exposed the fragility of traditional power structures—a lesson Portuguese revolutionaries internalized. By 1910, Portugal’s republicans, galvanized by Brazil’s example and hardened by their 1891 failure, capitalized on public outrage over royal scandals and economic crises to finally establish the First Portuguese Republic, completing a transatlantic cycle of rebellion that began with Napoleon’s invasion a century earlier.

Pink Map: Portugal’s Colonial Defeat and the Revolt of the Sergeants

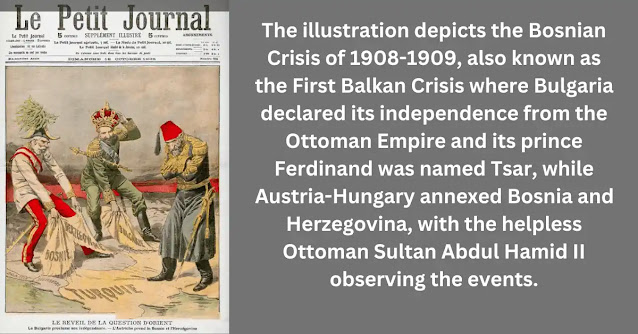

After Brazil gained independence from Portugal in 1822, Portugal’s overseas empire became mostly concentrated in Africa, with small territories in Asia such as Goa, Damão, Diu, East Timor, and Macau. In the late 19th century, Portugal focused on expanding its African territories, particularly in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). However, Portugal’s involvement in the European partition of Africa was limited due to its economic dependence on Great Britain. A movement advocating for colonial expansion gained momentum in Lisbon, and during the Berlin Conference Portugal Government claimed a large colony across Africa from Angola to Mozambique, and presented a map in 1886. That is called the famous Pink Map.

The ‘Pink Map‘ (Mapa Cor-de-Rosa), published in the Portuguese newspaper O Século in January 1890, was a key symbol of Portugal’s colonial ambitions in Africa. The name “Pink Map” originated from the color used to depict the territories claimed by Portugal on the map. This claim was recognized by France and Germany in 1886. However, Britain contested Portugal’s territorial claim in central Africa (now Malawi and Zimbabwe) and issued an ultimatum in 1890, demanding the immediate withdrawal of Portuguese forces from the disputed regions. This ultimatum threatened the use of British naval force and the long-standing Anglo-Portuguese alliance.

The dispute over the Pink Map had a significant impact on Portugal’s monarchy. It damaged the monarchy’s popularity among the people and contributed to the rise of republican sentiments. Additionally, there were suspicions that the British objections to Portugal’s claims were driven by their own interests, such as establishing a railway from Cape Town to Cairo. The collapse of the Portuguese monarchy was also influenced by pressures from individuals like Cecil Rhodes and British involvement in Africa.

The Pink Map crisis became more than a colonial dispute—it was the humiliation that radicalized Portugal’s military. The 1890 British Ultimatum, by crushing Lisbon’s African ambitions, exposed the monarchy’s weakness and directly inspired the Revolt of the Sergeants. Though the 1891 uprising failed, it crystallized a truth first revealed by the Pink Map’s collapse: Portugal’s old order was defenseless against foreign powers and unfit to lead a modern nation. This colonial shame, military discontent, and republican awakening would ultimately end the monarchy in 1910—fulfilling the revolt’s unfinished mission.

Anglo-German secret agreement on Portuguese Africa:

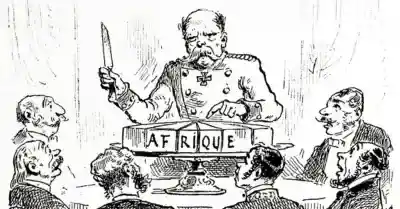

The 1898 Anglo-German secret agreement to partition Portugal’s African colonies emerged against the backdrop of growing tensions that had earlier fueled the Revolt of the Sergeants. This agreement came at a time when Portugal was facing financial challenges and the possibility of bankruptcy. Recognizing Portugal’s weakness, Britain and Germany seized the opportunity to secure their own interests in Africa.

According to the terms of the agreement, Britain was granted the lease of Delagoa Bay, a strategically important port located in present-day Mozambique. This allowed Britain to enhance its control over trade routes and maritime access in the region. Meanwhile, Germany acquired portions of Mozambique and Angola, expanding its colonial territories and influence in Africa.

The motivations behind this secret agreement were multifaceted. Both Britain and Germany sought to strengthen their positions in the race for African colonies during the era of European colonialism. Additionally, the agreement reflected the growing competition and tensions between major European powers, including Britain and Germany.

💻 You May Also Like:

- 450 Years of Portuguese Rule in Goa: A Colonial Legacy Explored

- The Berlin Conference and the Colonization of Africa: A Historical Overview

- Brazil’s Political Legacy: A Journey from Colony to Republic

- Glorious Revolution: A Democratic Revolt against Monarchy

It is important to note that this agreement had long-term implications. Less than two decades later, Britain and Germany would find themselves on opposing sides in World War I, with their colonial interests in Africa becoming contested battlegrounds. The secret agreement of 1898 played a part in shaping the complex dynamics and rivalries that would unfold in Africa during the early 20th century.

The Porto Republic Revolt: Soldiers Rise for a New Era

The Revolt of the Sergeants erupted in Porto during the pre-dawn hours of January 31, 1891, when a battalion of soldiers under sergeants’ leadership launched their rebellion. This pivotal event gained momentum as the rebels united with elements of the 10th Infantry Regiment at Campo de Santo Ovídio, though the 18th Regiment ultimately withdrew under their colonel’s orders. The Revolt of the Sergeants suffered from poor operational security, with numerous civilians and journalists witnessing preparations that should have remained clandestine.

Accompanied by regimental bands, the rebels marched to Praça de D. Pedro, where Alves da Veiga and other leaders proclaimed the establishment of the Republic from the balcony of the Porto City Council building. A provisional government was announced, and a red and green flag was raised.

The supporters in the square then aimed to seize the post and telegraph station, but their path was blocked by the municipal guard at the Church of Saint Ildefonso. Captain Leitão attempted to persuade the guard to join their cause but was overtaken by events. When shots were fired, believed to be from the crowd, the municipal guard responded with heavy gunfire.

A chaotic stampede ensued, and some soldiers and civilians sought refuge in the City Hall. However, with the assistance of army artillery and cavalry, as well as the 18th Infantry Regiment, which the rebels had tried to recruit, the municipal guard forced their surrender later that morning. The official report stated that twelve rebels and onlookers were killed, with 40 injured, but other sources suggest higher casualties.

From Defeat to Destiny: The Revolt of the Sergeants and Its Historical Legacy

The Revolt of the Sergeants in 1891 marked a pivotal moment in Portuguese history, profoundly impacting the nation’s political future. This daring uprising, led primarily by military sergeants and soldiers, saw rebels proclaim a Republic from Porto’s City Council balcony in direct defiance of the monarchy. Though the Revolt of the Sergeants ultimately failed to seize strategic strongholds, its bold challenge to royal authority galvanized republican sentiment across Portugal. The event demonstrated how mid-ranking military personnel could mobilize against the established order, setting the stage for Portugal’s eventual transition to a republic.

The aftermath of the revolt left a lasting mark on Porto and raised important questions about the future of republicanism in Portugal. The rebellion served as a prelude to subsequent republican movements and played a crucial role in shaping the political landscape of the country.

Despite being suppressed, the 1891 revolt had enduring consequences. It highlighted discontent within the military and showcased the growing support for republican ideals. The events of the uprising contributed to the momentum that eventually led to the establishment of the Portuguese Republic in 1910. As the first republican attempt to overthrow Portugal’s monarchy, the revolt’s legacy endures in modern Portuguese society, marking a pivotal turning point in the nation’s history.

Conclusion:

The Revolt of the Sergeants in 1891, though a military failure, became a defining moment in Portugal’s path to republicanism. Fueled by colonial humiliation, economic crisis, and inspiration from Brazil’s republican success, the uprising exposed the monarchy’s fragility and galvanized future revolutionaries. While the rebellion was swiftly crushed, its legacy endured—streets in Porto still honor its leaders, and its ideals paved the way for the 1910 revolution that finally toppled the monarchy.

The revolt also underscored the interconnected struggles of the Portuguese-speaking world, from Brazil’s abolition of slavery to Britain’s imperial interference in Africa. The Pink Map debacle and the Anglo-German secret agreement revealed how global power dynamics shaped Portugal’s decline, while the sergeants’ bravery proved that even failed rebellions can ignite lasting change. Their story remains a testament to how defiance, however brief, can alter the course of history.