The Other Great Game: Britain vs. the United States in Global Politics

At the dawn of the 20th century, the British Empire stood unchallenged, its navy ruling the waves and its influence spanning the globe. Yet the roots of its upcoming challenge stretched back to 1814, when the Treaty of Ghent (signed on December 24, 1814, in Ghent, a city in Belgium) officially ended the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain, but also planted the seeds for another conflict.

Between 1814 and 1960, an extraordinary transformation would occur as an unexpected rival emerged—not from Europe’s battlefields, but from Britain’s former colony across the Atlantic. This was no ordinary conflict of armies and empires, but a gradual revolution in global power played out through bank loans, treaties, and diplomatic maneuvers that would come to be known as The Other Great Game.

At its core, the conflict stemmed from America’s explosive economic growth and Britain’s desperate efforts to retain control over global trade and empire. World War I became the turning point: while Britain drained its resources, the U.S. emerged as its creditor, weaponizing dollars alongside battleships. Naval expansions, debt diplomacy, and competing visions for the post-war world—from Latin America to the League of Nations—revealed a stark power shift.

The British Empire, once dominant, now faced a rival that questioned its very legitimacy. Known as ‘The Other Great Game,’ this rivalry wasn’t fought with soldiers but with money and diplomacy. In 1900, the British Empire ruled a quarter of the world. By 1950, the United States had taken its place—without firing a single shot between them. The rivalry’s legacy endures in today’s geopolitics, where economic influence and soft power often eclipse territorial conquest.

💻 Table of Contents:

- The War of 1812: Igniting the Anglo-American ‘Other Great Game’

- Monroe Doctrine: Early Tensions in the ‘Other Great Game’

- The Silent Game: How America Won the Atlantic

- The Venezuela Crisis and British Retreat

- The Spanish-American War and Shifting Alliances: From Rivals to Partners

- Naval Arms Race and Economic Supremacy

- World War I: From Rivalry to Partnership

- Financial Dominance: America’s Ascendancy Over Britain (1919-1945)

- Korea as the Final Chessboard of the Other Great Game

- Suez Crisis (1956): The Final Humiliation and the Other Great Game

The War of 1812: Igniting the Anglo-American ‘Other Great Game’

The War of 1812, a conflict between the United States and Great Britain, was fought primarily in North America, particularly in Canada, and the Great Lakes region. The conflict was triggered by a combination of factors, including the British impressment of American sailors, trade restrictions on American shipping, and the desire for territorial expansion by the United States.

The War of 1812, while framed by Americans as a second war for independence, was fundamentally a result of Britain’s global struggle against Napoleonic France. After Britain’s naval victory at Trafalgar (a decisive battle against the French fleet) in 1805, they ruled the oceans. They made strict trade rules (called Orders-in-Council) that hurt American merchants and reclaimed about 6,000 American sailors to force them to serve in Britain’s navy (this practice was called impressment). These actions made Americans furious because they violated U.S. rights as an independent nation.

Britain was mainly fighting France in the Napoleonic Wars, but their harsh sea policies accidentally pushed America toward war in 1812. While trying to defeat France, Britain angered its former colonies, planting the seeds for the opening round of a longer “Other Great Game” between the two English-speaking powers. The war’s inconclusive end at Ghent (1814) left unresolved grievances that poisoned relations for decades, from disputed borders to British support for Native American resistance against U.S. expansion.

Although the Treaty of Ghent (December 24, 1814) reinstated the borders that existed before the war, the repercussions of the conflict were significant and lasting. It strengthened Canadian identity, reinforced American independence, and established patterns of Anglo-American competition that would evolve into the economic and diplomatic “Other Great Game” of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The war’s legacy lies not in territorial changes, but in how it set the stage for a century of complex relations between the former colonies and their mother country.

Monroe Doctrine: Early Tensions in the ‘Other Great Game’

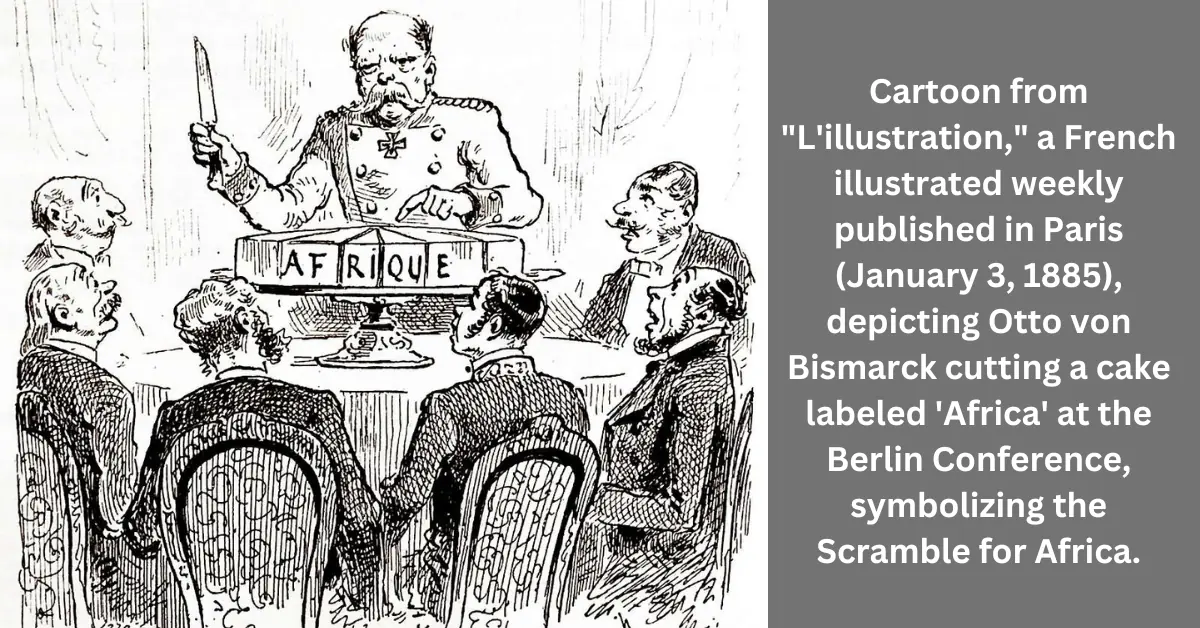

The 1823 Monroe Doctrine’s bold declaration of American hemispheric sovereignty marked a pivotal early round in the Anglo-American rivalry. While it appeared to target European powers, the real significance of the Doctrine was its gradual evolution into a tool for U.S. expansion, primarily against the British Empire. British leaders like Canning and Palmerston initially tolerated the policy as it conveniently aligned with their own anti-Spanish interests, but grew increasingly wary as American settlers and merchants began displacing British influence from Texas to the Caribbean.

Tension between the U.S. and Britain peaked in the 1840s during the Oregon boundary dispute. President Polk’s strong stance made Britain face a new reality: their former colony was now taking charge in areas that both countries had previously shared.

These early diplomatic conflicts set a stage for the “Other Great Game” up to World War I, where American goals gradually weakened British power through economic growth instead of direct military action. During the years of the Monroe Doctrine, Britain’s strong navy, while still dominant, started to help rather than limit American expansion. This situation dramatically changed during WWI when Britain needed American money and supplies, leading it to accept U.S. leadership in ways that would have been impossible in earlier times, marking a shift from rivalry in the Americas to a global power change.

The Silent Game: How America Won the Atlantic

The Oregon boundary dispute, known as the Oregon Question, was a 19th-century territorial conflict involving the Pacific Northwest of North America, primarily between the United States and Great Britain. Following the War of 1812, the dispute intensified as various nations, including Russia and Spain, withdrew their claims through treaties.

The Oregon Crisis of the 1840s represented a significant shift in the “Other Great Game,” turning territorial conflicts into a strategic diplomatic contest. When American expansionists famously demanded “54°40′ or fight,” they weren’t merely claiming land—they were asserting Washington’s equal right to shape North America’s future against British imperial interests. The eventual compromise at the 49th parallel established a crucial precedent: Britain would negotiate rather than wage costly wars to maintain its foothold against its former colony, setting the stage for future American gains through diplomacy rather than conquest.

Central America became the next testing ground, where Britain’s long-standing dominance faced new challenges from American ambitions. Britain’s established influence in Honduras and Nicaragua clashed with America’s belief in “Manifest Destiny,” leading to the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty in 1850. However, this treaty did not stop the U.S. from pursuing territorial expansion southward or from making unauthorized agreements with Central American countries.

Additionally, the treaty failed to address the issue of slavery, which caused significant divisions within the United States. Importantly, it gave the United States a way to counter Great Britain’s free trade thrust with its own growing focus on protecting American businesses. This dynamic conflict revealed another emerging step of the “Other Great Game”-American pressure followed by British agreements, all while avoiding direct military confrontation that might threaten London’s global responsibilities.

The Civil War years (April 12, 1861 – April 9, 1865) tested this fragile balance most severely, offering Britain its last realistic chance to curb American power. Confederate sympathies in Palmerston’s government nearly led to recognition of the South, while the Trent Affair and Alabama claims brought both nations to the brink of war. Yet Britain ultimately retreated, not because of Union threats, but because its leaders recognized an irreversible truth: even a divided America commanded enough economic and military potential to make containment impossible.

This reluctant neutrality proved decisive—by 1865, the United States emerged not just reunified but industrialized, setting the conditions for its eventual world leadership during the Great War that would finally decide the “Other Great Game’s” outcome.

The Venezuela Crisis and British Retreat:

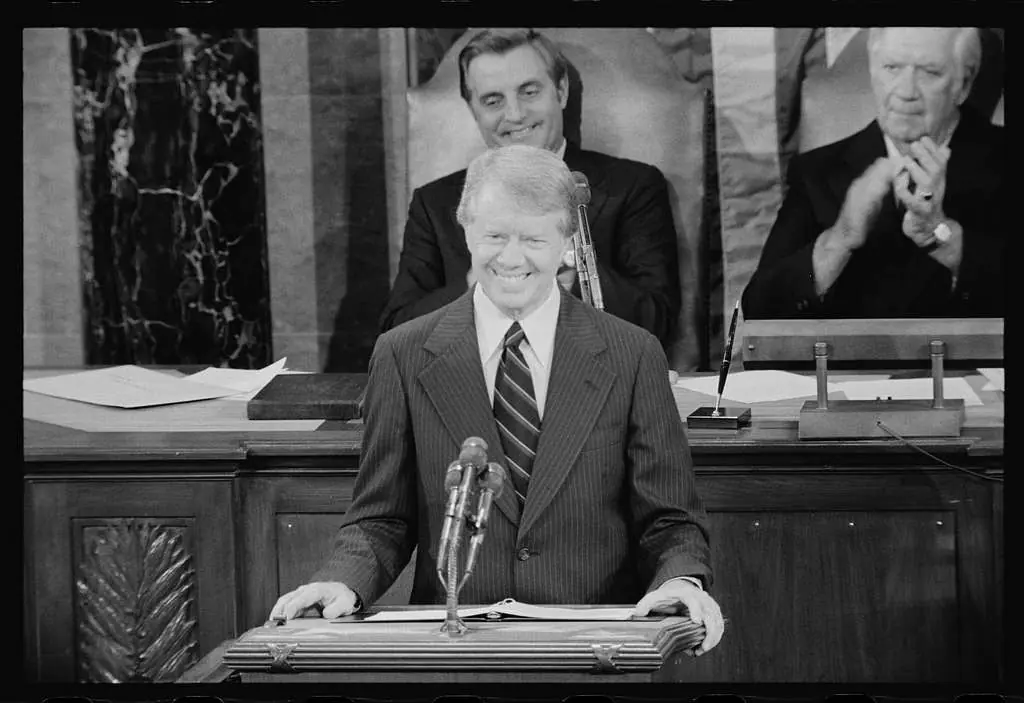

The 1895 Venezuela boundary dispute marked the moment when Britain formally acknowledged America’s hemispheric dominance. When Secretary of State Richard Olney declared that the U.S. was “practically sovereign on this continent,” Britain—still the world’s preeminent naval power—faced a stark choice: resist and risk conflict, or concede and preserve Anglo-American relations.

Lord Salisbury’s reluctant acceptance of arbitration was more than a diplomatic retreat; it was the final surrender of Britain’s century-long struggle to contain American influence in the Western Hemisphere. This episode crystallized the “Other Great Game’s” central dynamic—Britain’s gradual accommodation to U.S. ascendancy, not through war but through the irresistible pressure of economic and geopolitical reality.

The Spanish-American War and Shifting Alliances: From Rivals to Partners

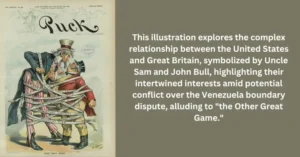

The U.S. victory in 1898 didn’t just dismantle Spain’s empire—it revealed Britain’s strategic realignment in the “Other Great Game.” While Europe condemned American expansion, Britain alone remained neutral, even quietly supportive, as U.S. fleets seized the Philippines and Cuba. This tacit cooperation reflected London’s cold calculation: with Germany rising as a shared threat, America’s growth could no longer be resisted, only harnessed.

The war’s aftermath saw Britain abandon its traditional role as balancer against U.S. power, instead conceding naval parity in the Caribbean and accepting America’s Pacific ambitions. The “Other Great Game” was entering its endgame—not with British defeat, but with its pragmatic pivot toward Atlantic partnership, setting the stage for their World War I alliance and the final transfer of global leadership.

Naval Arms Race and Economic Supremacy:

By the early 20th century, the “Other Great Game” had shifted decisively in America’s favor. The naval arms race, illustrated by President Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet, alongside Wall Street’s rise as the leading global financial center, represented the peak of a century-long conflict. Britain, though still draped in imperial grandeur, now faced an undeniable reality: the U.S. had surpassed it in industrial capacity, credit leverage, and naval ambition.

💻 You May Also Read:

- Manifest Destiny: Geopolitical Doctrine behind U.S. Expansion

- The Monroe Doctrine: American Plan for the Americas

- The Spanish-American War: Roots in US Envision of Great Power Status

When World War I erupted, Britain’s dependence on American loans and supplies formalized this transition, turning a once-contentious rivalry into an asymmetrical partnership. By 1918, the “Other Great Game” was over—not with a clash of arms, but with the quiet triumph of economic and diplomatic ascendancy. The baton of global leadership had passed across the Atlantic, reshaping the world order for the century to come.

World War I: From Rivalry to Partnership

World War I became the final act of the “Other Great Game,” where financial power proved more decisive than naval might. As Britain bled its treasury dry, Wall Street emerged as the Allied lifeline—J.P. Morgan’s loans totaling $2.5 billion (equivalent to $50 billion today) made the U.S. not just a supplier but a creditor holding Britain’s survival in its hands. Germany’s submarine warfare and the Zimmerman Telegram merely accelerated the inevitable: America’s entry in 1917 transformed the conflict from a European war into a transatlantic transition of power.

The war’s aftermath revealed the full reversal of the 1812 dynamic—where Britain had once blockaded American ports, now Washington dictated peace terms at Versailles. The Royal Navy still ruled the waves, but the Federal Reserve now governed global capital flows.

This marked the subtle conclusion of the “Other Great Game”: while no treaty officially relinquished the British Empire, by 1919, its financial dependence on the United States signified that geopolitical dominance had permanently shifted across the Atlantic. The rivalry that began with wooden frigates in the War of 1812 concluded with the U.S. holding 40% of the world’s gold reserves, while Britain struggled under $4.7 billion in war debts to its former colony. The age of American hegemony had begun.

Financial Dominance: America’s Ascendancy Over Britain (1919-1945)

After World War I, America used money power to dominate Britain. The U.S. demanded full repayment of war loans, crushing Britain’s economy. When Britain tried squeezing Germany for cash, the system collapsed. The Federal Reserve’s policies made the dollar supreme, while Britain lost its gold reserves. By 1931, Britain abandoned the gold standard—a humiliating sign of decline.

During World War II, the United States initiated the Lend-Lease program in 1940, supplying military aid to Allies like the UK, despite remaining officially neutral until 1941. President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought to support nations fighting against Nazi Germany while navigating legal and public resistance to U.S. involvement. The Lend-Lease Act (An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States) allowed the U.S. to provide supplies without immediate payment, fostering economic ties and laying groundwork for a new international order. This strategic move not only aided Britain but also solidified America’s emerging dominance, marking a significant shift in global power dynamics.

By the end of the war, Britain was $21 billion in debt to the U.S., and American firms acquired British industries at low prices, completing the economic takeover in the “Other Great Game. Without a single battle between them, the U.S. replaced Britain as the world’s leading power. The “special relationship” became America’s way of managing Britain’s decline. Moreover, the American Marshall Plan, implemented after World War II, exemplified the U.S. strategy in ‘the Other Great Game’ by aiding European recovery and solidifying American influence, thereby reshaping global financial and geopolitical landscapes in favor of U.S. dominance.

Korea as the Final Chessboard of the Other Great Game:

In the mid-nineteenth century, Korea remained isolated until American ships began appearing along its coasts. The first documented encounter occurred in 1853, but mutual incomprehension marked these early meetings. Tensions escalated with the arrival of the American merchant vessel General Sherman in 1866, which resulted in violence and the Korean perception of Americans as barbarous invaders. Subsequent American military actions in the late 1860s further entrenched Korea’s isolationist policies and fostered extreme distrust of foreign powers, particularly the United States.

The signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1882 marked a turning point, establishing formal diplomatic relations and leading to a more positive perception of the U.S. among Koreans. American missionaries and diplomats played significant roles in fostering goodwill, contributing to Korea’s modernization.

The strategic calculus shifted decisively after 1894, when Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War exposed the limits of U.S. and Chinese influence in Korea. Britain’s 1902 alliance with Japan effectively endorsed Tokyo’s continental ambitions, while the U.S.—despite early sympathy for Korean independence—ultimately prioritized relations with Japan over defending Korean sovereignty.

The 1905 Taft-Katsura Agreement was a deal where the U.S. agreed to allow Japan’s control of Korea in exchange for Japan recognizing American control over the Philippines, marked the final move in this geopolitical chess game. Korea’s annexation in 1910 was the final move in the “Other Great Game” in Asia. It showed how the power struggles between Britain and the U.S. could lead to smaller countries being sacrificed for bigger strategic deals—a phenomenon that would happen many times throughout the 20th century.

Suez Crisis (1956): The Final Humiliation and the Other Great Game

The Suez Crisis marked the definitive end of Britain’s imperial dominance and the full ascendance of the U.S. in the Anglo-American “Other Great Game.” When Britain, France, and Israel invaded Egypt to seize the Suez Canal, Eisenhower crushed their ambitions not with armies but with financial warfare—halting U.S. aid and threatening to collapse the pound sterling. This humiliation proved the new rules of power: economic leverage, not colonial force, now dictated global influence. The crisis also exposed Britain’s vulnerability to Soviet pressure, as Moscow’s nuclear threats compounded Washington’s financial assault, forcing a humiliating Anglo-French retreat.

The aftermath cemented America’s supremacy. Eisenhower’s 1957 Doctrine formalized U.S. hegemony in the Middle East, explicitly filling the vacuum left by Britain’s disgrace. By positioning America as the region’s anti-communist guarantor—demonstrated by the 1958 Lebanon intervention—the U.S. completed its takeover of Britain’s traditional spheres of influence. Suez thus became the last act of the “Other Great Game,” where financial and diplomatic weapons achieved what cannons once did, transferring global leadership from London to Washington without a shot fired between them.

Conclusion: America's Quiet Triumph

The “Other Great Game” ended not with battles, but through America’s diplomatic and technological supremacy. Hollywood outshone British prestige, and Silicon Valley’s advances surpassed British industry. The change from “British Petroleum” to “BP” showed a loss of identity, while Britain’s nuclear independence slipped into America’s influence. The 2016 Brexit referendum highlighted Britain’s new position in an American-dominated world. The League of Nations, conceived by Woodrow Wilson, aimed to dismantle imperial power structures, replacing them with a U.S.-guided system of collective security—bypassing traditional great-power rivalry.

This power shift is notably invisible—there was no formal transition when American English became the global standard, nor any monuments for U.S. data dominance under the Five Eyes alliance. The “special relationship” obscured the fact that Britain had become a junior partner in an American-centric order. The “Other Great Game” quietly transitioned, with its victors too powerful to boast and its vanquished too reserved to object. From the War of 1812 to today, Anglo-American rivalry concluded not with a bang, but with the subtle influences of Hollywood, technology, and a shared understanding of power.